Propulsion

Propulsion Choices begin with Fuel and End with Politics

The maritime industry’s elusive quest to achieve so-called ‘zero’ emissions continues. Where it ends is not a one-size-fits-all discussion.

By Robert Kunkel

Looming Large in the Center Porthole

The year-end maritime industry discussions tend to move away from global influence and back drift to national and domestic debates. As this happens, a positioning of a relatively small group of American owners and operators prepare for the upcoming business year and markets. The propulsion debate continues to be future fuels based upon sustainability and climate change. And it is not only what you burn in your engine, but also what you will be trading domestically in your barges and tankers.

The current domestic fleet serving the non-contiguous trades and the smaller ferry fleets serving surrounding ports and cities made fuel decisions months, if not years ago, as first movers and without the extreme IMO pressure.

The discussions differ from the global fleet of companies continuing to chase emission standards with the path to reach ‘zero’ and satisfy the IMO projections for 2030. The added impact of The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), a carbon credit program that limits carbon dioxide emissions, has not only led to the emergence of a plethora of early alternative fuels, but also a demanding financial influence that can be both profitable and detrimental. How the system rates an operation within the “cap & trade” allowances affects the operator’s carbon intensity rating and the cost to play the game. That process is also about to change with the adoption of FuelEU entering into force January 1st, 2025.

Meanwhile, back in the Colonies

The economic influence has not taken effect in the U.S. domestic fleet as propulsion and fuel decisions, at this point, are not economically ‘enforced’ or the result of trading allowances. The current domestic fleet serving the non-contiguous trades and the smaller ferry fleets serving surrounding ports and cities made fuel decisions months, if not years ago, as first movers and without the extreme IMO pressure.

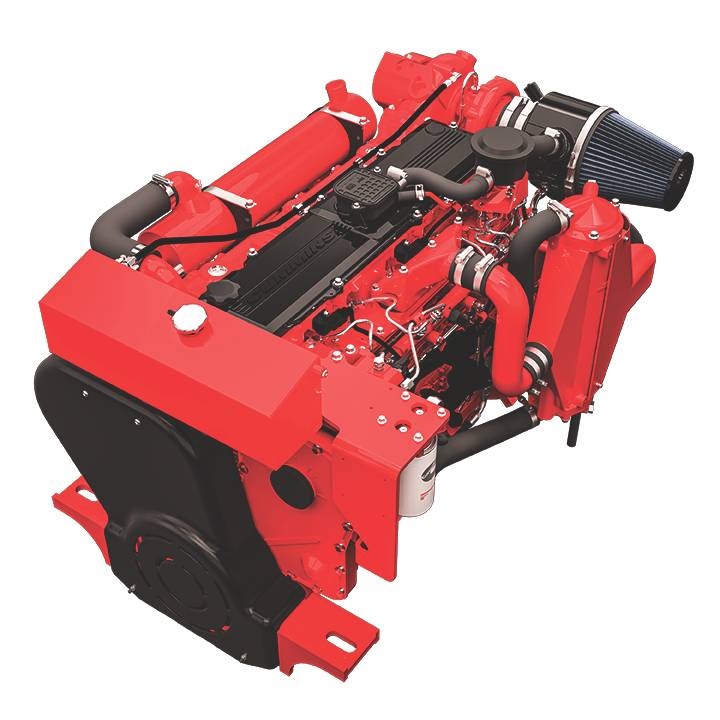

… we have been working closely with Cummins Engines on propulsion systems that employ hybrid applications and incorporate both their G-Drive diesel engines and more recently their Accelera program. Cummins understands that sustainability and the ‘zero emission’ quest is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution.

Some embraced LNG with a reported 60% reduction of CO2 and 100% reduction of particulate matter. Others, in markets with limited energy requirements, moved to Hybrid and EV where ‘zero’ could eventually be achieved, albeit only in smaller vessels and niche coastal movements. These decisions were based not only upon clean air and water, but also on available capital and higher operating costs realized in our domestic trades. The U.S. arguably had – and still has – a better understanding of the term ‘transition’ and the actual time the assets would operate prior to reaching ‘zero’.

With the Federal election and a change in the Administration many are wondering what direction the U.S. Maritime sector will take as voluntary carbon credits are discussed and fossil fuels move back into the driver’s seat. We may see ammonia being discussed only on the back of a household clean agent bottle, and not being burned in your internal combustion engine.

Nuts & Bolts: real metrics, real issues

We are just weeks away from the five-year anniversary of the global Sulphur cap. A debate continues about the environmental benefits of the regulation and the global adoption of scrubbers. These are decisions based solely on the comparative operating cost of existing black oil versus the cost of low sulfur marine diesel oil. The environmental detriments are now taking two paths with some nations. First, some question the ocean damage caused by open loop scrubber system discharges and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). At the same time, other scientific reports indicate the reduction of sulfur in the atmosphere has not reduced warming, but instead, contributed to it.

This is an onion with many layers to it. Let’s start with the markets of lower energy requirements. Smaller ferry vessels and inland movements are a significant part of this discussion. Many U.S. cities are now issuing requests and grant opportunities to build and operate fully electric vessels (EV) ferries. As many as twelve, and possibly more projects are in the wind; requesting designs and/or starting construction. More will come.

Locally, and in our shop, we have been involved with battery and diesel electric propulsion in the U.S. market for over ten years. And, we have been working closely with Cummins Engines on propulsion systems that employ hybrid applications and incorporate both their G-Drive diesel engines and more recently their Accelera program. Cummins understands that sustainability and the ‘zero emission’ quest is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution.

… the Hybrid application allows the vessel to be always in control of its power requirements and with a full redundancy of propulsion safety on the water. As we continue to discuss the propulsion path, it must be understood that the major oil companies have simply advised that diesel oil will be around for decades to come. Hybrid, as well.

For example, our projects with Cummins have delivered ‘zero’ during operation and reduced emissions and energy use during charging. Couple that with reduced maintenance of the combustion engines (in two, 5-to-10-year projects, the engines have had only oil and filter changes), along with the ability to now be fuel agnostic, this has made those projects very successful.

Many smaller projects look to full ‘EV’ capability at conception. When developing the operating tempo, cities and/or private entities soon discover that shore charging can be restrictive. The existing terminals and utilities cannot provide the necessary power through the grid and with that, cannot maintain passenger or cargo turnaround within the prescribed schedule. Conversely, the Hybrid application allows the vessel to be always in control of its power requirements and with a full redundancy of propulsion safety on the water. As we continue to discuss the propulsion path, it must be understood that the major oil companies have simply advised that diesel oil will be around for decades to come. Hybrid, as well.

Deep Water

On the larger domestic blue water deep draft fleet, the choice has been LNG and it continues to be LNG on recent containership contracts and deliveries; both foreign and domestic. Over 29% of the global fleet is using LNG or reporting to be “LNG ready.” We determined early on that LNG was a transition fuel. That said; the transition period was difficult to predict and still is. With global alternative fuel infrastructure still in question, LNG will be here and available well beyond the near future.

As the industry makes attempt to develop fuels to accomplish ‘zero’, many have determined that only Small Modular Reactors (SMR) and nuclear propulsion will be the choice. Of the two initial ship designs working through commercial nuclear system, in both Korea and the United States, the hull and cargo they are attached to are both large capacity LNG tankers. Despite how the environmental groups look at LNG – it is here to stay through this transition as an energy provider.

Let’s take a deeper look at nuclear as its commercial introduction goes well beyond technical issues and wrestles with a perception problem due to the major accidents onshore reported through the decades. We take the position that the U.S. nuclear Navy has a safety history that is near flawless.

There are more than a few SMR designs being developed and most variations are concerned with cooling. In the U.S. market, Light water cooled (LWC) systems are preferred, as they are less complicated and include a neutron moderator. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is currently completing license reviews for LWR SMR.

Other designs employ liquid metal, gas and the Asian models have moved forward with Molten Salt. Kepco in Korea is working with Molten Salt, as is Hyundai on their commercial ship design. SMR designs use either low-enriched uranium (LEU) or high-assay low enriched uranium (HALEU). LEU is roughly 5% uranium 235 (U-235) and the HALEU derivative is between 5% and 20% of U-235. HALEU is preferred as it leads to smaller designs and longer operating cycles. In no uncertain terms, it is expensive and the financial models being built to analyze a 25-year fuel supply on a commercial vessel is no easy task. All of the steps required to gain approval are heavily regulatory-based, well beyond Class, the U.S. Coast Guard, or that matter, any Flag State. The review will include the transshipment of uranium, national security, DOE approvals and Cyber Security. And, those restrictions have been in place for U-235 for decades.

No Easy Answers

One of the problems with meeting IMO 2030, 2040 or 2050 is the influence of the financial models, incentives or penalties along with infrastructure and distribution of these new fuels. Technical decisions take into account safety, trend analysis and long-term effect on machinery. The history is simple to follow. We adjusted operations to burn heavy fuels. The adjustment continued with low sulfur and LNG. The subsequent warp-speed jump to burn ammonia and hydrogen did not and has not taken the trend analysis into account. With that rush, the market is also experimenting with Bio fuel blends. All of this has the potential to assist in the transition period emission reductions, but also comes with operational alerts.

North America is working towards BIOLNG/ RNG, BIO diesel, FAME (used cooking oil) and the definition of ‘green’ hydrogen and ‘green’ ammonia. Many of these fuels and blends are being traded commercially in the foreign chemical fleets. In fact, six of our domestic chemical ships routinely carry many of the products. As the transition continues, we need to review the capability of our domestic ATB and tanker fleet to determine if we have U.S. flag tonnage that can distribute these new fuels coast-to-coast, as one or more fuel choices are approved and reach mass adoption.

Finally, a recent industry report indicated that one of the ‘bio’ blends included a fuel made from Cashew nutshells, a low-cost renewable fuel reportedly being delivered in Singapore and Rotterdam bunkering ports. Operational problems have been reported, including fuel sludging, injector failure, filter clogging, system deposits and corrosion of turbocharger nozzle rings.

Yes – I’m going to go there – That is simply NUTS

About the Author

Robert Kunkel is president of Alternative Marine Technologies and First Harvest Navigation. He served as the Federal Chairman of the Short Sea Shipping Cooperative Program under the DOT’s MARAD from 2003 until 2008. He is a past VP of the Connecticut Maritime Association and a contributing writer for MarineNews and Marinelink.com