Safety

Reimagining the Coast Guard

The more than half decade that has passed since the inception of the subchapter M towboat rule affords an up-close-and-personal look at how it is going. The scorecard is a mixed bag.

By Pat Folan

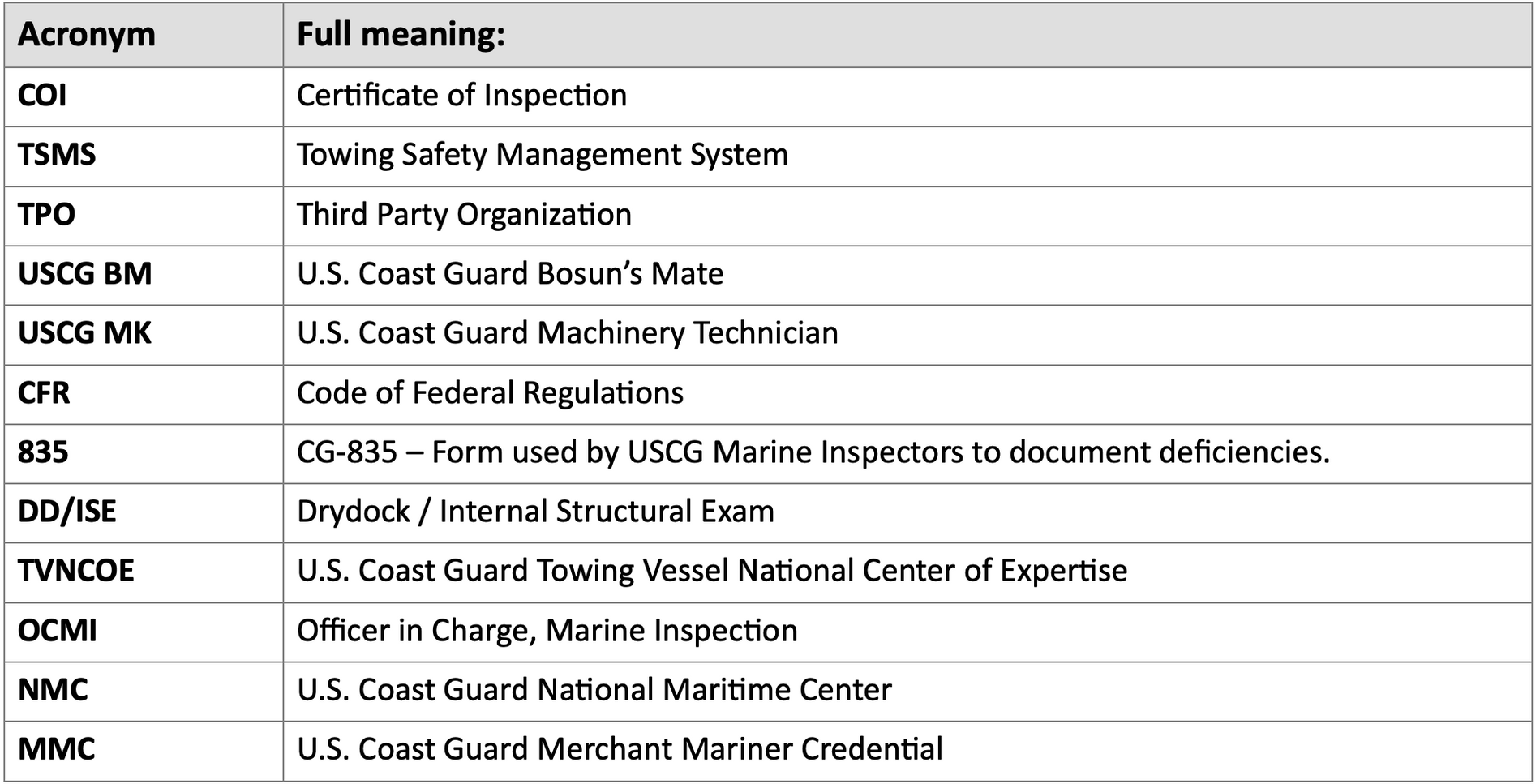

More than six years ago, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) began inspecting towing vessels for compliance with the new towboat rules; specifically, 46 CFR Subchapter M. It has been a long road to compliance with many starts and stops, and much learning on both sides of the law.

Has it been a success? If success is measured by Certificates of Inspection, then yes. Roughly four-fifths of the towing vessels that were afloat in July 2018 have their COIs. But the remaining 20% do not. In some cases, the boats weren’t physically able to pass the test and that is a huge measure of success. We don’t have to worry about the crew members on those boats and the danger to the environment that many of them posed.

Success is also hard to measure when you have two tracks to compliance. I believe that the companies that went the TSMS route initially – and really embraced it – are safer. But employee retention makes a fully developed safety culture a challenge for even the best companies.

On the other hand, some didn’t make it because the owners simply had enough government regulation and sold the boats to those better positioned to comply. Or, they just scrapped the boats. By and large, these boats weren’t the pride of anyone’s fleet, but they worked. It has been sad to watch companies fold because of the one-size fits all approach to compliance of the USCG. We worked with the owner of a three-boat company in the northeast that one day just threw the towel in. The boats were good, had even gotten their COIs, the crews were exceptional, but the owner didn’t want (or need) the USCG in his face.

Measuring Success: a moving target

Success is also hard to measure when you have two tracks to compliance. I believe that the companies that went the TSMS route initially – and really embraced it – are safer. But employee retention makes a fully developed safety culture a challenge for even the best companies.

The second track, the USCG option, should not exist if the safety of mariners and the environment is what we are trying to achieve. For example, the vessels are required to have a Health & Safety Plan on board. This is a subset of policies and procedures that make up a TSMS. My company attends roughly 265 USCG Option inspections per year. Since 2018, I have only witnessed one marine inspector looking into the Health & Safety Plan. He asked the crew general questions about the plan and then moved on to recordkeeping. Otherwise, the inspectors are blissfully unaware of the Health & Safety Plan. It is a fair question to ask: If the inspectors don’t care, why should the crew?

The crews and shoreside personnel at a TSMS Option company are trained on the TSMS and audited annually. There are consequences for failing to understand the TSMS. It can mean the boat will be tied to the dock by the TPO that has oversight. Even the USCG gets in on the act and can remove a company’s TSMS Certificate if they find systemic issues. The loss of a TSMS certificate at a five-boat company can mean the loss of employment for about 60 people until the boats can be re-inspected as USCG Option boats.

Since 2018, I have only witnessed one marine inspector looking into the Health & Safety Plan. He asked the crew general questions about the plan and then moved on to recordkeeping. Otherwise, the inspectors are blissfully unaware of the Health & Safety Plan. It is a fair question to ask: If the inspectors don’t care, why should the crew?

That inspection is a deep dive into the boat’s systems and a quick look at recordkeeping. But that’s it. The USCG inspectors are not trained or qualified to audit a Health & Safety Plan, so it never gets done.

Decoding the Language of Inspections

The USCG created two classes of vessel companies. One that only has to survive selective scrutiny by USCG inspectors and one that must undergo audits and surveys with third party auditors and the USCG inspectors. And if you doubt the selective scrutiny part, just watch an inspection where a USCG BM has to inspect the machinery space, or an MK has to inspect the wheelhouse and navigational equipment.

The USCG has no way to provide consistency within its inspections. It can’t do it well within a single unit and, arguably, it fails across most sectors.

After six years, everyone with a vessel knows where to go with the boat for an easy inspection. This is reminiscent of the ‘venue shopping’ done by mariners in the years prior to the consolidation of some responsibilities at Coast Guard regional exam centers into a central office in West Virginia. Driving up and down the east coast, mariners could hit four or five REC’s until they got the answer that they wanted on a license examination or renewal.

By easy; I mean fair and fast. There is nothing worse for the owner and crew than to have the government van pull up and four or five blue suiters pile out with the CFR books. At that point you know that the boat won’t be making any money that day. Most crews know that they must split up and follow the inspectors around the boat. And the good crews know to argue with some of the findings. Not all deficiencies are from the correct Subchapter.

To be fair, the USCG is struggling mightily with recruitment. Young people are not attracted to serving. The good news is that for the first time since 2017, the USCG has met its recruiting goals, but they are still working with a deficit.

How long will it take the USCG to train the new recruits that manage to survive Cape May? When can the industry expect to see better customer service? Like it or not, the Coast Guard is in the customer service business.

After six years, everyone with a vessel knows where to go with the boat for an easy inspection. This is reminiscent of the ‘venue shopping’ done by mariners in the years prior to the consolidation of some responsibilities at Coast Guard regional exam centers into a central office in West Virginia. Driving up and down the east coast, mariners could hit four or five REC’s until they got the answer that they wanted on a license examination or renewal.

Data Collection: for the greater good?

And while we are talking about measuring, why is it that every little thing that happens on a towing vessel (or any certificated vessel) must be reported to the USCG? Technically, it’s not supposed to be every little thing, but most USCG units err on the side of caution and request reports for everything and then they say they’ll weed them out. But why? What is the point? Nothing useful ever comes of it. The USCG is sitting on a mountain of data from all sectors of the marine industry, but they don’t provide useful insights to the industry that they regulate. The FAA and OSHA also collect data, and their databases are searchable and useful. If I wanted to see trends across a certain industry in a specific geographic area, I could get the data from OSHA. But, if I was looking for the number of times a particular diesel propulsion or generator engine fails on towing vessels, I am out of luck. We as taxpayers spend a lot of money on the USCG, but it doesn’t seem to go to upgrade the systems that the industry could use.

Why isn’t every 835 that is issued by the USCG online in a searchable database? It would be a great learning tool to be able to see what deficiencies exist. At my company we track 835s and the inspectors that wrote them. That’s because it’s nice to know the inspector’s pet peeves and even better to be able to share that information with customers in the areas that the inspectors transfer into.

The same issues apply when it comes to appeals. They live and die at the unit level. Because we work across many sectors and districts, we learn about appeals and file them away in case we ever need them. But most people are unaware that an appeal has been filed and what the disposition is. A win for industry should be shouted from the mountaintops. Making the appeals public helps mariners and the Coast guard, alike. They’ll spend less time writing 835’s if they know there are successful appeals to the deficiency they are pondering, and industry will also not waste anyone’s time appealing something that has been shot down a few times.

The appeals process should be rewritten. I can commit a crime and be out on appeal on personal recognizance, but the boat can’t work until the appeals process is completed. And it’s hard to believe that it is a fair system because one officer is highly unlike to overturn another officer’s decision. Their mutual progress up their career ladders arguably depends on helping each other.

We are repeatedly told by inspectors around the country that they do not have enough inspectors to do their job in a timely manner. The backlog is bad enough that we had a company come back to the TPO Option from the USCG Option because it lost 30 days waiting on the USCG in the previous year. And only the US Government would double the cost of the inspection and provide less for the owner’s money.

Easy Fix

The inspections are one area where it is not too hard to find a good workaround. That’s because the USCG should work with the TPO’s. Most companies can deal with the annual inspection. It’s not easy, but it can be done because generally after the USCG leaves you go back to work. But Drydock and Internal Structural Exams are a big problem. Getting shipyard availability in some areas is hard. If the boat or barge ahead of you needs extra work, then you must wait. At the same time, the USCG wants a minimum of 14 days’ notice. Hence, if you were supposed to come out on December 1st and the yard holds you off until the 6th, but doesn’t tell you until the 4th, then you will have missed your exam on the 1st, and may have to wait until the 18th for the inspectors to arrive. Throw a holiday or two in there and you are not going to work anytime soon.

If you are unfortunate enough to be hauled out in at least one certain Coast Guard district, then you can only wait on the stands until the inspectors arrive and then they will tell you what to do. Under any circumstances, do not start any work. This “my-way-or-the-highway” attitude in this sector is strangling the shipyards. If you have a choice, you do not haul out at any of those yards if you are a USCG option boat. Fortunately, most other Sectors will let you begin work if you document it well and are in a reputable yard. With the TPO Option, if you come out next Saturday, then you will have a drydock exam completed, and holidays don’t matter.

This fix is easy. Add a hybrid option for USCG Option companies to use a TPO Drydock/Internal Structural Exam program. It would immediately free up inspectors and soothe over vessel owners and yard owners ruffled feathers.

This isn’t to say that the DD/ISEs would be any easier than with a USCG inspector. Far from it. As someone that performs these exams, I don’t cut corners. Lives are on the line. If it is bad, it’s bad. Crop it out and renew it. Unlike the USCG inspector, I know it costs money to go through the exams and repairs, and I do care. But I care more about the guys sleeping and living on the boat. And I’ll tell you what to expect to do at the next drydock, so that you can budget for it.

It also fair to ask why the USCG decided that loadline vessels that were subject to a DD/ISE every five years now must have a DD/ISE every 2 to 3 years? ABS was doing a good job managing that system and then the USCG came along and added a significant financial and time burden to the owners.

Partnerships require care and mutual understanding – and possibly, real change

As a first step to improving the inspection process and, for that matter, the outcomes, it would be enormously useful to teach the inspectors as to what the industry entails, and what the vessels do, and how they do it. We are constantly told that the industry and the USCG have a partnership, but it seems like a very one-sided relationship. One sector has decided that all towing vessels with grating over the steering gear on the aft deck must have rails around the bulwarks area with the grating. It’s a nuisance for the towboat operators but it is nonsensical for the vessels that tow astern. The wire comes off the winch and goes across the aft deck to a barge. The rails would last a few seconds at best. This lack of understanding of how an ocean-going towing vessel operates is dangerous and costly for the owners.

The maritime industry needs personnel. A useful on-the-job educational effort could involve assigning young ensigns and lieutenants to work – or at least ride and observe – on the boats, even for a short period of time.

We speak frequently with the U.S. Coast Guard Towing Vessel Center of Expertise, and they provide us with valuable information and guidance. Unfortunately, though, they can only do that. The OCMI’s have the final say and in some sectors that we work in, the inspectors tell us that they do not pay any attention to the TVNCOE. For some reason, we are all expected to believe that the OCMIs are subject matter experts in their given geographic areas even though they have never sailed in the waters or in most cases never lived in the area for more than a few years. Becoming a subject matter expert takes time and experience. If they truly partnered with the people in their areas that had the time and experience, we would all be better off. Why not trust the department with Expertise in its name?

It might be time to reimagine the USCG. It wouldn’t be that hard to do. The nation’s fifth uniformed service has, for generations, been tasked with a multi-mission portfolio with tepid funding support that has forced them, in many instances, to “do more with less.” The United States Coast Guard excels at many things; among them lifesaving, maritime interdiction, servicing aids to navigation and the list goes on. Let them continue to be world class in those areas and look for ways to hand off the other functions where they are not.

“The opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of MarineNews magazine.”

About the Author

Pat is a USCG Master of Towing Vessels, Near Coastal, Inland and Western Rivers. He was a USCG-Towing Safety Advisory Committee Member (Sub Committee Co-Chair for Steel Hull Repair and Operational Stability tasks.) He is an ISO 9001:2008 Certified Lead Auditor, ISO 19011:2011 (E) Internal Auditor ISM Internal Auditor (RINA), SAMS Accredited Marine Surgeyor - Tugs and Barges, USCG Uninspected Towing Vessel Examinder Course. He is also a Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer, Six SIGMA Green Belt (Villanova) and has completed the Train-the Trainer course at Chesapeake Marine Training. He is a graduate of St. Bonaventure University with a BA in Mass Communication. He previously owned a towing company based out of Boston.