Interview

David Parker, Head of Hydrographic Programs, UKHO

Inside the new UK Center for Seabed Mapping

David Parker, the Head of Hydrographic Programs at theUK Hydrographic Office (UKHO) discusses the rationale behind the new UK Center for Seabed Mapping, with insight on seabed mapping and its connection to the Blue Economy.

By Greg Trauthwein

There are few more prestigious names in the world of hydrography than the UKHO, the world’s largest center for hydrography.UKHO support a staff of 900 in Taunton, UK, with a small contingent in satellite offices in Singapore and Washington, DC. Its ADMIRALTY Maritime Data Solution product portfolio includes a series of around 18,000 electronic navigational charts which arecarried by around 90% of the world's trading fleet, made available to mariners worldwide through a through a distribution network of 182 distribution offices. In addition, UKHO are the primary charting authority for just over 60 other nations.

“We deliver six separate hydrographic programs; programs of data collection activity and capacity building supporton a worldwide basis, either alone or in partnership with other organizations,” Parker said.

Various recent global initiatives have highlighted the importance of charting world’s waterways to support the growing ‘blue economy,’ but there is a caveat.

“It's fair to say that the interest in the understanding of the benefits of mapping the world seabed has definitely increased,” said Parker. “I think it's also fair to say though, that perhaps the funding, particularly from governments, to undertake that activity has not increased with that level of interest necessarily.”

It is perhaps that dearth of funding, with government’s traditional focus more on traditional terrain, as the reason that progress has been slow to evolve.

“When I started my career in the early '90s, I think we'd mapped less than about 10% of the world's seabed. That figure has grown (to around 20%). There has been progress, but it's slow progress,” said Parker.

But the tides are changing with initiatives such as Seabed 2030, which recently received a big boost when the US officially signed for the project at the United Nation Oceans Conference via NOAA.

“That's really helped raise the profile of seabed mapping. But more to the point, the benefits to be derived from having better mapping of our oceans and seabeds,” said Parker.

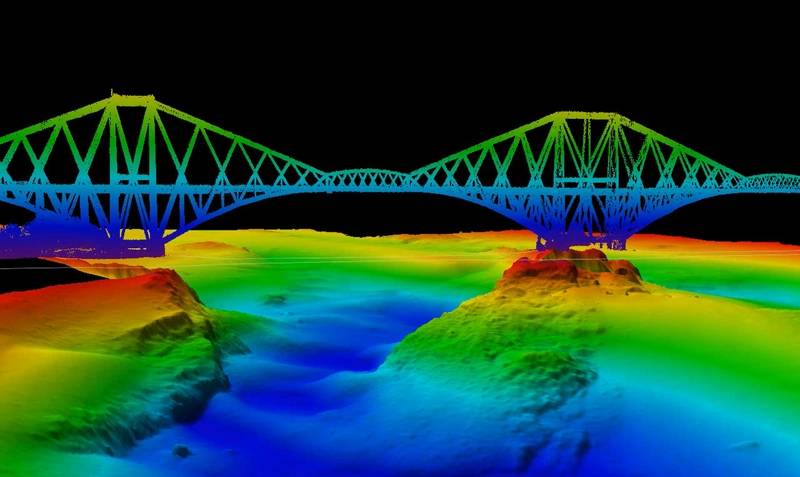

Image courtesy UKHO When I started my career in the early '90s, I think we'd mapped less than about 10% of the world's seabed. That figure has grown (to around 20%). There has been progress, but it's slow progress. David Parker,

Head of Hydrographic Programs, UKHO

The New UK CSM

In early July, UKHO invited UK-based public organizations involved in seabed mapping who share common interests in optimizing the UK’s national maritime assets to become a member of the new UK Center for Seabed Mapping (UK CSM). Administered by the UKHO, UK CSM was submitted as a UK Government Voluntary Commitment to the United Nations at the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal in June 2022.

“At the first meeting, we had 22 government organizations represented, and we hope to increase this number in the future, as there's more than 30 in the community,” said Parker.

The UK CSM has a remit to increase the coverage, quality and access of seabed mapping data collected using public funds, as well as to better promote it as a critical component of national infrastructure. Created to spearhead a coordinated approach to the collection, management, and access of seabed mapping data – and to champion a more integrated marine geospatial sector in the UK – the UK CSM has established three initial working groups which members can join and contribute to: National Data Collaboration, International Data Collaboration, and Data Collection Standards.

“Quality marine geospatial data is essential for almost every activity undertaken in the marine domain, including maritime trade, environmental and resource management, shipping operations, and national security and infrastructure,” said Parker. “More interoperable and usable data will support more informed ocean governance and policy, which in turn will support greater innovation and prosperity.

According to Parker, while the Center is new, work has begun and “we're now working through a process of having these organizations formally sign up to be members of the UK Center for Seabed Mapping (via MOU). We’ll be meeting again in October (2022) and getting down to work really at the working group level to start on items such as national coordination.”

He said work will begin also on unified data collection standards and specifications, as “our real aim is around ‘collect once, use many times,’ with the aim of having data that is interoperable with all the other organizations involved.

He said “we hope to really be making a measurable difference to things like collection rates and overall efficiency of all the programs and things like that, as early as next year.”

While Parker and his team are starting with government organizations, the long-term vision is “to look to bring in academia and the private sector; because a lot of the activity that goes on, perhaps even the bulk of the activity that goes on, is outside of government.”

Bigger picture, outside even the new UK CSM itself, Parker considers the impact of improved, free flowing data on the waters in and around a country.

“Just like having an electricity network or a water network, data in itself, mapping, topographic mapping, hydrographic mapping in the maritime space is a key part of national infrastructure,” he said. “I know a number of ports, for example, where improving information and knowledge of the seabed has allowed ship operators to increase the cargo imported or exported during each visit. Depending on what's being carried, being able to reliably increase your draft through taking onboard extra cargo, even by four inches, can be worth tens of thousands of dollars per visit.”

When you add up the number commercial vessel trips multiplied by the number of ports and the number of ships operating globally – then throw in the advantages inherent in having accurate fish habitat mapping, for example – the real economic impact to a country’s economy starts to grow exponentially.

“I think all-in-all it's about understanding in terms of the blue economy, it's about understanding that data asset to be part of your core national infrastructure,” said Parker. “Just like on land, where we use topographic maps for just about every meaningful activity and nobody even thinks twice about it, we don't have the same level of mappingavailable to us for the maritime environment.”

https://www.admiralty.co.uk/uk-centre-for-seabed-mappingThe Subsea Technological Tsunami

All industries have gone through a technical tsunami in the past generation, as computing speeds have risen and costs have plummeted. The hydrographic market has benefitted too, with increased ability to collect and disseminate data and information on what lies beneath the world’s waterways.David Parker, the Head of Hydrographic Programs at the UK Hydrographic Office (UKHO), weighs in with his pick of the top technology innovations in the last 30 years.

“The technology shift in my career has been huge,” said Parker, who started his career in the early 1990s. “When I started, we predominantly used single beam echo sounders to map the seabed, effectively creating a bathymetric profile of the seabed underneath the vessel, wherever you went.”

That approach left many gaps in information, where “we had to use some of our skill as surveyors to estimate where we could safely leave the gaps and where we had to fill in.”

While there were imaging tools to help fill the gaps, Parker said the big shift was the move to multibeam echo sounders and bathymetric LiDAR systems, which unlike that single beam isolated profile, generates a full picture of the seabed, said Parker.

“I think the second pick is a fairly obvious one for me, the advent of global navigation satellite systems,” said Parker. “It's easy to forget that GPS on your phone or GPS on your ship is a relatively recent thing. When I started in the '90s, the United States GPS was just starting to become available for civil use, but it was limited in terms of its constellation.”

At the time GPS was intentionally degraded by the US government, and “what could have been 10-meter accuracy became 50-meter accuracy, for example,” said Parker. “We were still using land-based microwave ranging systems and the like, which took a lot more effort to set up, manage and maintain. [Back then] you would spend a quarter of your day sorting out where you are. These days, you flick a switch and it just happens and nobody thinks about it anymore.”

“Of course, the outcome of this technology is perhaps much more significant for the users of our products,” said Parker. “I'm thinking of it from the surveyor perspective out there mapping the seabed. The fact our users can now navigate a meter level accuracy easily anywhere in the world, almost instantaneously, is really quite remarkable.”