Green corridors: The catalyst for the decarbonisation of maritime supply chains.

A new framework, created by the Lloyd’s Register Maritime Decarbonisation Hub, aims to get the industry sharing best practice, helping to scale up smaller decarbonisation successes to large-scale ocean-going shipping.

In an urban design context, ‘green corridor’ is a term used to mean interlinked pathways or cycle routes running through a city that are rich in trees and plants, thereby providing benefits to both residents and natural wildlife. By extension, the concept was first applied to transport by the European Union in 2007 with the aim of developing integrated, efficient and environmentally friendly movement of freight between major hubs and by relative long distances.

‘Green corridors’ in transport normally make use of advanced technology and seamless intermodal connectivity – or ‘co-modality’ – to achieve energy efficiency and reduced environmental impact, which given today’s escalating concern over climate change essentially means ensuring decarbonisation and sustainable supply chains.

Lloyd’s Register (LR) is well aware that decarbonisation is now the number one issue facing the shipping industry, its own research having shown that zero-emission vessels need to be entering the world fleet by 2030. This in turn requires shipping to be planning and building new shipboard solutions and land- based infrastructure immediately.

There is a problem, however, since zero- emissions solutions have so far only been deployed in niche applications, such as remote ferry routes in Scandinavia, while solutions for large scale ocean shipping are not yet established. This dilemma has created uncertainty across the sector, with lots of different alternative fuels and propulsion technologies – and evolutionary pathways to arrive at the same – under discussion.

LR has identified the need for reliable and impartial guidance in the face of so many conflicting opinions on alternative ways to decarbonise, for the benefit not only of ship owners and operators but also fuel suppliers, shipbuilders and equipment manufacturers, policymakers and regulators, financiers and insurers, and more.

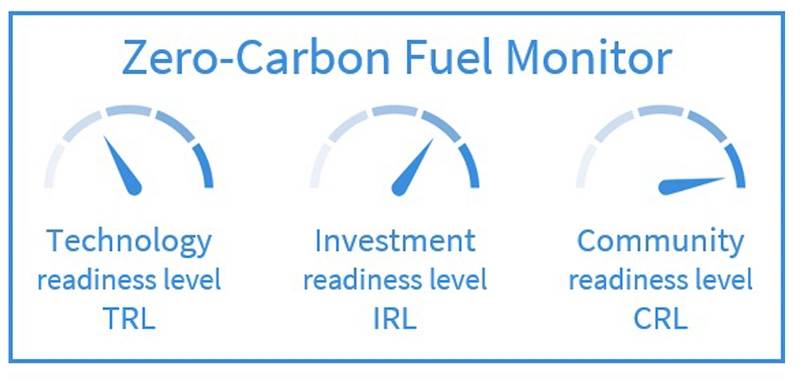

As a result, LR has this year introduced a new Zero-Carbon Fuel Monitor framework, an evidence-based tool to assess the readiness of the most promising zero-carbon fuels and related technologies that could play a role in getting the entire shipping industry to zero emissions by 2050.

Zero-Carbon Fuel Monitor

The framework analyses the current state of development of different alternative fuels and the infrastructure that their require, giving an indication of progress towards industry-wide adoption. It does this by awarding each potential solution three different ratings: for Technology readiness level (TRL) – how close the technology is to being proven, scalable and safe? Investment readiness level (IRL) – whether the business case is robust enough to attract investment; and Community readiness level (CRL) – how prepared people and organisations are to adopt the new solution.

The methodology was created by the LR Maritime Decarbonisation Hub, a new initiative set up jointly by Lloyd’s Register Group and the Lloyd’s Register Foundation late last year and now led by Programme Manager Charles Haskell.

“The Hub will provide a basis for closer collaboration between stakeholders and a platform for sharing the results of decarbonisation initiatives so that we as an industry continuously learn from previous projects and evolve,” Haskell said upon his appointment in January 2021.

Also joining the Hub this year as Marine Decarbonisation Consultant was Dr Carlo Raucci, who moved over to LR from University College London (UCL) where he had previously completed an LR-sponsored PhD on the potential of using hydrogen to decarbonise shipping.

Raucci explains that the Hub is divided into five different workstreams – Policy, Technology, Investment, Safety and Sustainability – all dedicated to “working with other stakeholders to provide new insights into a sustainable energy transition in shipping using safe and commercially viable vessels.” And “at the core of the Hub”, he adds, is the Zero‑Carbon Fuel Monitor.

The framework looks at the different technology, investment and community readiness levels along the length of the supply chain – from the production of fuels, including the resources used, through their transportation, storage and bunkering, to usage on board ships and the propulsion machinery involved. “The entire supply chain is in consideration,” Raucci stresses.

Carlo Raucci

The methodology results in three separate final scores – for TRL, IRL and CRL – for each fuel “We have tried to aggregate as much as possible but producing a single score loses meaning,” he says.

And rather than picking any likely ‘winners’ in terms of alternative fuels, the Decarbonisation Hub has been using the framework to “identify bottlenecks and where more effort is needed to progress the readiness level of a particular fuel.”

Raucci gives the example of ammonia, where “some unknowns with safely handing the fuel onboard ships mean the TRL score is quite low, meaning “if we are able to provide some new insights on these issues we are advancing the TRL readiness level of the fuel as a whole.”

Investment challenge

One of the focus of Raucci’s own work is the Investment workstream, and here he observes that the IRL score for most fuels is “very low” for three main reasons.

Firstly, any fuel is going to be much more expensive than current fuel so some sort of policy lead is needed to ‘close the gap”, he believes.

Secondly, the use of technologies such as electrolysis or direct air capture / carbon capture and storage to produce zero carbon fuels is still lacking in “demonstrations of application at a scale than can be used for shipping. So more work is needed, particularly for hydrogen, ammonia and methanol, he says.

And thirdly there is the supply vs. demand problem that new fuels will not be made available until there are ships that can use them, and vice versa.

Of course, ports have a role to play as well in shipping’s decarbonisation effort. Reducing dwell times of ships by advising them well in advance on when they should arrive at berth for fastest turnaround – so-called Port Call Optimisation – is just one solution, with electrification of port equipment and use of solar energy other developments that are increasingly taking place.

Then there is the whole question of them facilitating the bunkering or even production of alternative, low-carbon fuels. Decarbonisation Hub leader Haskell has cited the example of the ports of Antwerp, Zeebrugge and Hamburg all working with industrial partners to establish hydrogen import chains, saying “The next step is to look at the shipping trade between these ports to create ‘green corridors’.

Charles Haskell

“Ports have the potential to be a catalyst for the shipping industry’s zero-carbon transition”, he added, “but it is a chicken and egg scenario. Ships will need the fuel so the ports will need to supply it, but if the ports are using the fuel for other purposes, then the port infrastructure changes around that fuel.” He gave the example of a port that might be importing hydrogen, perhaps as a result of national decarbonisation policy, that could choose to use the fuel to power its cranes, cargo trolleys and localised shipping like harbour tugs and pilot vessels under its control, and then look at scaling up this supply to support the deep-sea shipping industry.

“Once more than one port is supporting the infrastructure and there is trade between these ports, then that trade can start going through an energy transition,” Haskell observed, adding that it is vital that we see more of these types of pilots, involving multiple stakeholders building up fuel supply chains, this decade “so they can be scaled up to meet the 2050 ambitions”.

Singapore feeder study

Meanwhile, to help visualise how the transition to alternative fuels might take place in practice real world, LR has embarked on its own pilot study, scoping out a suitable location and area of the shipping industry where “first movers might set up a green corridor or green supply chain”.

Raucci takes up the story, explaining how after some preliminary research it was decided to focus on the containership sector and the segment of small boxships or feeders serving intra-Asian routes particularly from Singapore towards Hong Kong. “This was because it was thought that the energy transition of the feeder fleet has the potential to act as catalyst for all the other ships calling in Singapore or Honk Kong,” says Raucci, “and because there’s a high volume of traffic between these major hubs” – thereby corresponding with the idea of green corridors as major trade arteries where collaboration among different stakeholders would enable new investments.

“The aim of this project is to progress the IRL levels and eventually unlock small-case commercial trials on the path to reach zero-emissions by 2050 by providing more details on how the identified feeder fleet in this area could transition to zero-carbon fuel. We wanted to start to understand what challenges would be involved for a given type of fleet and to define how that fleet would transition to other fuel.”

Some 200 vessels are involved in the target study, which will also look at what developments will be needed on the supply side for the production, transport and delivery to a port like Singapore of alternative fuels. “The end goal of the project will be to evaluate a common cost for both the target fleet and infrastructure,” says Raucci, “which will include analysis of the cost of producing both ‘blue’ and ‘green’ ammonia in different southeast and neighbouring countries.”

Already nearly 60 different configurations of production and supply have been identified, he adds, and assessment of the methodology to be used is currently being finalised, “at which point we can engage more with other stakeholders”. The project started three months ago and is expected to be finished before the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP 26) due to take place in Glasgow from 31 October through 12 November.

“This particular project focuses on the investment challenge,” Raucci says, “but everything is linked, including, for example, the technology challenges of scale or the safety aspects of handling new fuels or the community acceptance of having ships carrying fuels like hydrogen calling major ports close to high-density urban populations.” In the final analysis such problems can doubtless be overcome, however, he believes – as has happened with widespread acceptance of LNG as a marine fuel despite initial safety fears.

“By applying the innovative Zero‑Carbon Fuel Monitor framework we at LR believe can really progress the sustainable transition of the shipping industry,” he concludes. “It’s pushing us towards innovation and is quite extensive, giving us holistic ‘big picture’ answers. We’re very proud of how it’s coming along and hope it will have a significant impact.”