Training & Education

Navigating Icy Seas

Safely Navigating Icy Seas

Back in 2005, Ulf Ryder, President and Chief Executive of Stena Bulk, said: “It takes as much time to train an ice master as it does a brain surgeon.”

By Wendy Laursen

The IMO Polar Code was adopted in November 2014 with training requirements that a working group meeting in Buenos Aires in November 2023 agreed need revision. Argentina, along with co-sponsors Canada, Chile, Georgia, Malaysia, Philippines, South Africa and Turkey, recommended that competency standards for seagoing personnel and instructors should be revised and training courses updated.

Ice navigator Captain “Duke” Snider, participant in both the development of the Polar Code and the Buenos Aires meeting as the subject matter expert for The Nautical Institute, says too many mariners have been turning up with a warm, fuzzy feeling only to find that they have no idea what to do when they encounter icy seas.

Snider, founder of Martech Polar, says incidents such as the grounding of the Akademik Ioffe in 2018 are a reminder of the dangers. When ran aground, the Akademik Ioffe was sailing through narrow waters in a remote area of the Canadian Arctic that was not surveyed to modern hydrographic standards and where none of the crew had ever been before.

Source Marine InstituteWe focus on the group actually working together in a very interactive way and then switching roles so everyone gets to play a part in not only making decisions but also knowing when to add to a decision as well. - Captain Chris Hearn, director of the Centre of Marine Simulation at the Marine Institute of Memorial University

Source Marine InstituteWe focus on the group actually working together in a very interactive way and then switching roles so everyone gets to play a part in not only making decisions but also knowing when to add to a decision as well. - Captain Chris Hearn, director of the Centre of Marine Simulation at the Marine Institute of Memorial University

A recent study of incidents that occurred in the Canadian Arctic between 1990 to 2022 found a significant positive correlation between vessel accidents and sea ice concentration. The researchers said their results underscore the complexity of Arctic maritime operations in the face of climate change and highlight the urgent need for adaptive strategies, continuous monitoring and targeted policy interventions to ensure the safety and sustainability of future Arctic shipping.

Ship traffic has increased substantially along major Arctic routes, such as the Hudson Strait, Baffin Island and the Northwest Passage, driven by the consistent decline in sea ice, and Snider says conditions are no longer as predictable as they once were. “Climate change is making a huge difference,” he says. “Every year is different, and that’s hard for a lot of inexperienced mariners and operators to grasp.”

Under the Polar Code, seafarers can obtain a basic or advanced certificate of proficiency. While that training includes general operational considerations and an introduction to sea ice, its coverage of ice navigation is limited and based more on theory that practice, says Snider. Additionally, some flag state approved courses haven’t received the due diligence they deserve. There’s some schools that conduct the two five-day courses over just two days.

The Nautical Institute developed a training and certification scheme focused on ice navigation in 2017 which maritime training facilities can become accredited to teach. It builds on Polar Code and STCW requirements by providing additional elements that ensure certificated officers are both trained and experienced in the maneuvering of vessels in ice.

Source Martech PolarEvery year is different, and that’s hard for a lot of inexperienced mariners and operators to grasp. - Captain Duke Snider

Source Martech PolarEvery year is different, and that’s hard for a lot of inexperienced mariners and operators to grasp. - Captain Duke Snider

All the training certifications include simulator time, but Snider says that while those from Wärtsilä and Kongsberg are of a notably high standard, some others merely color bits of water white instead of blue without simulating the physics associated with wind, current and ice thickness. “Where the rubber hits the road with ice simulation is actually simulating a ship contacting the ice and what happens then – the ship jerks, stops and heals. A good simulator does these things so you know when you’ve screwed up.”

Kongsberg’s K-Sim Navigation simulator includes an advanced ice module enabling simulation of several different ice types, and the instructor can choose the location and size of the ice that a student experiences. Both crushing and friction factors are included that will affect the vessel's acceleration, speed and maneuverability through the ice.

Kongsberg Digital, Maritime Simulation, VP Product, Martin Reiten, says the maneuverability, speed and ability to break the ice are model-dependent, making it possible to achieve realistic training objectives for different vessel types. Linnaeus University in Sweden, the Canadian Coast Guard and the Maritime Institute of Memorial University in Canada are some of Kongsberg’s many customers who utilize the ice functionality to the fullest.

Captain Chris Hearn, director of the Centre of Marine Simulation at the Marine Institute of Memorial University, emphasizes the importance of simulator realism both visually and in the underlying physics. Some of the push for this comes from navies, he says, which along with commercial vessels are becoming more active in areas such as the Northwest Passage.

Virtual reality headsets have great potential for enhancing training outcomes. However, Hearn says a lot of the Marine Institute’s ice navigation training is focused on team work using full mission bridge simulators. “We focus on the group actually working together in a very interactive way and then switching roles so everyone gets to play a part in not only making decisions but also knowing when to add to a decision as well. We do this so that they experience how information is flowing on the bridge.”

It's important for ice navigators, and therefore trainers, to consider regional differences: ice and operational conditions in the Baltic are not the same as the on Arctic or Antarctic, says Hearn. Other things to consider are marine protected areas which can change location following sea mammal and bird migration patterns and the introduction of S-100 e-navigation enhancements. The additional data being made available via S-100 is expected to filter down to the navigation equipment that is used on ships, and it will also need to be incorporated into training programs.

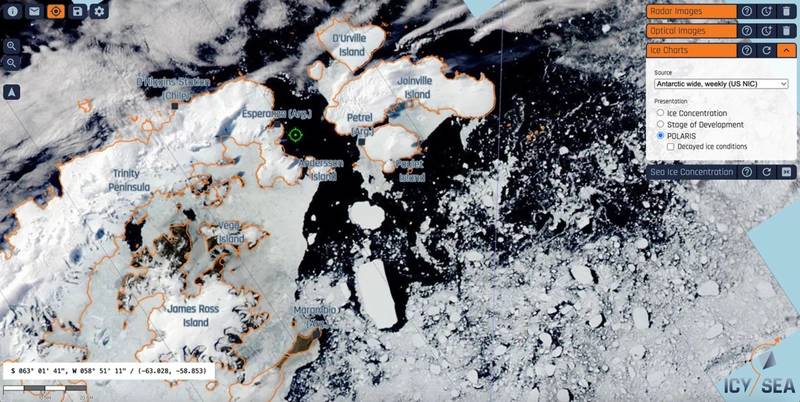

The app IcySea by Drift+Noise provides near real time map-based sea ice information for ships sailing in both the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Dr. H. Jakob Bünger, Research and Consulting at Drift+Noise, says the various research projects the company’s staff are involved in are designed to provide information that can be layered on to the satellite imagery and other data provided by the app.

Coming up in the app’s development is the ability to characterize the age and type of the ice in the imagery and the use of sea ice drift models to update imagery between refreshes of the satellite data. A voyage planning system that will help navigators choose optimal paths through icy waters depending on their vessel’s capabilities is in the early stages of development.

Digital tools and training simulators continue to advance in sophistication, but it’s not yet clear when the IMO will revisit its Polar Code training requirements.